Significance:

The historic importance of the site is rooted in the layers of activity and events that have occurred within the official boundaries of the park, on property immediately adjacent to it, and within the neighborhood that SWEPCO Park serves. This history begins during the Civil War, continues in the early twentieth century during the period of regional industrialization, and again during the Civil Rights Era of the late 1950’s and 1960’s. Besides its history being unnoticed, the park’s narrative takes on contemporary significance due to intentional neglect by the city. The preparation of this survey is intended to substantiate the need for the preservation of SWEPCO Park.

Description:

SWEPCO Park is named for the corporation that donated the 5.3-acre parcel of land to the City of Shreveport. The park is located at the northern end of Allendale neighborhood about a mile west of downtown. Initially laid out in the late nineteenth century, Allendale was one of the first communities developed outside of the street grid that defined the original settlement of Shreveport. These early neighborhoods were identified by topographical conditions. St. Paul’s Bottoms, primarily a black community, was located at the western edge of downtown. Highland, originally a white neighborhood, was south of the city, across a low flood plain. Allendale, situated above the Bottoms on the other side of Western Street, was originally known as Cutliff Hill. Its name was changed early in the twentieth century to Allendale, after Henry Watkins Allen whose estate, while briefly serving as governor at the end of the Civil War, was located here.1

Topography is also a defining characteristic of SWEPCO Park. At its highest point along the southern edge bounded by Patzman Street, the elevation is 222 feet above sea level. From here the site drops off steeply to the park’s northern edge, approximately aligned with Chester Street at 172 feet. A change of grade of 50 feet over a distance of 340 feet is distinctive even in the more hilly terrain of northwest Louisiana, a state whose highest summit is only 535 feet above sea level. The region’s geomorphology is river alluvium and levees, created by the seasonal rise and falls and floodwaters of the Red River upon which Shreveport was founded. The bluff that constitutes the park’s landform can be characterized as a naturally formed levee.

Likely contributing to the wide dispersion of these levee formations across the region was the continual change of course of the Red River. From its beginning as a United States territory, this part of Louisiana was known for the massive logjams that developed on the river from north of Shreveport downstream to an area near of Natchitoches, a city founded in 1714 by French colonists. As a result of the impaired flow of the 1360-mile long Red River water coursed through many channels across a plane as wide as twenty-five miles. In addition to the raised levees a series of lakes was also formed, creating what today would be called a massive wetland. In 1832 Captain Henry Miller Shreve began clearing the logjam, referred to as the Great Raft, opening up the river to navigation in 1839.2 One of these subsidiary channels was Twelve Mile Bayou, now serving as an outlet for Caddo Lake. Another was Cross Bayou, a waterway dammed in 1926 to provide a reliable source of water for Shreveport.3 The confluence of these two meandering waterways is in the lowland north of SWEPCO Park. The lake, or cooling pond for the adjacent power plant, was carved out of an oxbow between the two bayous.

Northwest Louisiana and parts of east Texas sit on a geologic formation called the Sabine Uplift. This rise from deep beneath the earth’s surface allowed for the entrapment of vast quantities of fossil fuels from the Cretaceous Period. Located northwest of Shreveport, the Caddo Oil Field was discovered in 1905.4 An oil boom ensued across Caddo Parish contributing significantly to the growth of the city of Shreveport. Some of these fields remain productive today. A 1935 Sanborn Map of Allendale indicates an oil well and several oil tanks just north of the site, across Chester Street. Two additional oil wells are shown on a 1950’s USGS map on blocks in the neighborhood a few hundred yards south of the site.

Another historical map labels the area immediately northwest of the park as an oil field. The soil of the site is Susquehanna Clay, “a heavy silty clay, of such a structure as to allow the passage of water with comparative freedom. The color is prevailingly brown to reddish-brown, and the soil is always very shallow, having an average depth of 4 inches. The subsoil is quite deep, and is composed of a heavy red clay which has a comparatively open structure.”5 Native vegetation of this soil type is a good growth of hardwoods, including oaks, hickory, elm and ash. A field survey of existing trees in the park confirms that this is the case.

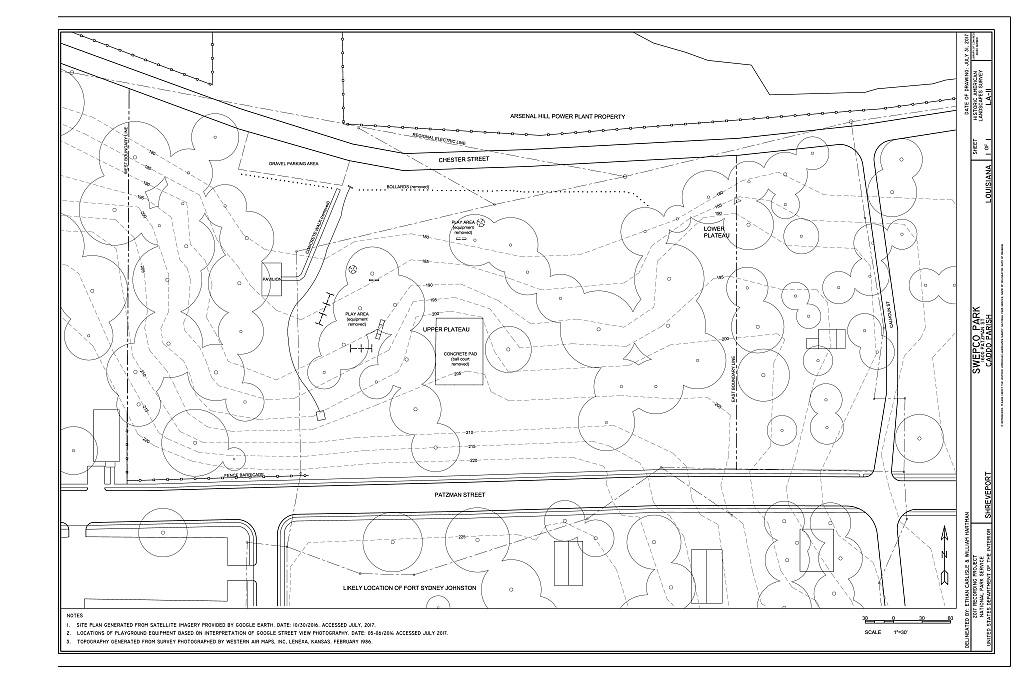

Though it is likely that portions of the original soil layer were disturbed, the site’s topography prevented the type of residential development typical of the neighborhood. One area of probable disturbance is the park’s southern edge at the time that Patzman Street was paved with curbs and gutters. Maps from the first half of the twentieth century show that most of this portion of the street was unpaved despite the existence of structures on its southern side. Another area of possible soil disturbance due to recontouring of the site is the plateau in the park’s center whose deteriorating concrete paving once served as a basketball court. (See Figure 1) A walk of the site suggests that most of the park remains in a natural state. One element of infrastructure that was added is culvert that appears to follow existing contours across the lower portions of the park. A concrete drainpipe feeds this culvert with water from storm sewers on the streets above but there is little indication any significant disturbance of natural conditions.

Figure One: View at sunset towards northwest from concrete pad that previously served as a basketball court. The prospect from this plateau at the center of SWEPCO Park is across the cooling pond of the Arsenal Hill Power Plant to the tree-lined bayou beyond. During the Civil War and until the construction of the power plant this view would have included an oxbow in the vicinity of the visible power pole and an island where the pond is now.

Figure Two: View at sunset towards northeast from below central plateau. Visible is SWEPCO’s Arsenal Hill Power Plant across a corner of the cooling pond. The hill in the distance at the photo’s center is Arsenal Hill, where the Confederate Army stored its military weaponry adjacent to Twelve Mile Bayou for ready access to Red River.

Figure Three: View looking east from the pavilion. In the foreground is a portion of the drainage swale. Beneath the stand of trees was the location of the playground equipment that was removed in 2016. Above the play area is the central plateau. This landform is possibly a natural levee, modified for defensive purpose during the Civil War, and later to provide a flat area concrete pad for the basketball courts that were built for the park.

Figure Four: View looking south from near the pavilion. To the left is the storm drain outlet and meandering swale. At the top of the hill is Patzman Street. According to historical maps the trees visible at the top of the hill are adjacent to the location of Fort Albert Sydney Johnston.

Today this publicly owned park represents a rare example of a native landscape within the heart of an important city in the southern United States. The bluff condition that characterizes SWEPCO Park played a role in the defense of Shreveport by Confederate forces during the Civil War. The extant landforms thought to have served in this defense are the plateau mentioned in the previous paragraph, and a second flat area in the northeast corner of the park. From this position one can observe a clear path to the summit of the hill above that was the location of Fort Albert Sydney Johnston, one of three forts constructed outside of the defensive walls of the city. (See Figure 8) From this summit, now a vacant lot, one has an excellent prospect from a northeasterly position across to the west-southwest. The two plateaus within the boundaries of the park, may have served as intermediary defenses between enemy forces and the stockades of the hilltop fort.6 No archaeological evidence exists to confirm whether these two plateaus were naturally formed or modified to serve as part of a defensive installation.

Figure Five: View from near the top of the hill near Patzman Street looking east to the trees surrounding the central plateau.

Figure Six: View downhill of the wooded west edge of SWEPCO Park showing the mature and dense understory growth.

Figure Seven: View from lower plateau near northeast corner of the park. Chester Street is visible and is approximately twenty-five feet below. Trees, dominated by slippery elm, surround this relatively flat area with a great view across the cooling pond.

Figure Eight: View from the lower plateau looking south up the more gently sloping hill on the east side of SWEPCO Park. The trees on the left side of photo are along the east boundary line. Visible above is a residence on Patzman Street with crape myrtles in bloom.

Today a tree canopy covers at least one third of the park. An aerial image from 1989 on Google Earth, shows the same distribution of trees across the site, however with less coverage due to nearly thirty more years of growth. There are four stands of trees across the park. The densest of these is at the western edge of the park where the topography is steep and the understory has been allowed to grow undisturbed. A second stand of approximately ten mature trees is located across the drainage swale from the first group on the west flank of the central plateau. Moving east across the site is the most substantial grouping of trees forming a continuous canopy that snakes up and down the slope and around the base of the second plateau located in the northeast corner of the park. There is something of a hedgerow along the park’s eastern boundary. Across the fence that is in place along a portion of this edge, is a scattering of smaller, more ornamental trees typical of a domestic landscape.

Except for the western edge of the park, there is no understory growth beneath the trees. A mix of grass species covers the majority of the site except where the tree canopy is too dense to sustain growth. This layer of groundcover has typically been maintained by mechanical mowing, though this critical effort has been neglected recently. On a tour of the site on July 18, 2017, the grass cover in open areas ranged from twelve inches to more than thirty-six inches along the edges of drainage swales. A botanist was not consulted to help in the identification of the species of grasses. The author was able to identify that the two dominant tree species are Overcup Oak (Quercus lyrata) and Slippery Elm (Ulmus rubra). The elms were mostly in the eastern half of the site, with a cluster around the lower plateau. Additional species composing the tree canopy include: Willow Oak (Quercus phellos), Water Oak (Quercus nigra), White Oak (Quercus alba), Cedar Elm (Ulmus crassifolia), Hackberry (Celtis laevigata), and Black Gum (Nyssa sylvatica). One Pecan (Carya illinoinensis) was identified near the pavilion on the west side of the park. While an exact number was not tallied, the total tree count of the park is approximately forty-five to fifty. A number of vines were identified growing against the trunks of trees, particularly within the understory on the park’s western edge. The predominant vine appeared to be Poison Ivy (Toxicodendron dermatitis). A survey of site fauna within the park was not conducted. However, the author was able to determine the presence of mites of the rombidioidea family, commonly known as chiggers.

SWEPCO donated the property to the City of Shreveport for the purpose of recreational, cultural and aesthetic development in particular for use and enjoyment of the public. The Shreveport Journal records a $10,000 investment in SWEPCO Park by the Citizens Committee for Community Improvement for the installation of playground equipment.7 The basketball court was installed on a plateau in the center of the park. To build the required concrete surface, it is likely that what was an existing natural form was re-contoured to accommodate the rectangular expanse of the court. The squared corners at the north end of the court are suggestive of this point. Several pieces of playground equipment were positioned in the shade of trees just west of and below the basketball court.

These included two swing sets with a total of ten swings, a merry-go-round, a climbing structure, and a bench. Typical of playgrounds from this period, there was no safety surface installed beneath them. Northeast of the court in a relatively level part of the park, also beneath the canopy of a majestic oak, were a second merry-go-round and bench.

Following this initial investment in the park, a 30’x20’ pavilion was built at the wooded edge on the park’s west side. The structure consists of three bays of steel posts supporting a shallow sloping metal roof. A gutter collects rainwater across the lower edge diverting it in scuppers located at both corners. The floor is concrete. The sides are completely open, allowing for maximum breeze through the pavilion. Its backside is nestled nicely into the sloping woods behind it. On the front a concrete walk was installed from the central bay leading down the gentle slop to a parking area adjacent to Chester Street. Basic amenities included at least two picnic tables and a container for trash. A small utility pole near the pavilion suggests that at one time there was possibly a lamp to illuminate the immediate area. Another feature of SWEPCO Park was a line of wood bollards separating the recreational territory within the park from a continuous parking strip about 30’ wide along the street at northern edge.

Except for the spectacular views from within the park, the only other remarkable features are the electric transmission lines that run through the site. These operate at two scales. A neighborhood line runs in a straight line across the lower edge of the site, entering the park from the northeast corner, making a right angle turn near the pavilion to Patzman Street above. A larger scale line entering the site from the same corner is of little impact. A single, distinctive pole of corten steel is situated in the parking strip approximately 100’ from the eastern boundary of the park.

Conversations with residents of the Allendale neighborhood have revealed the value of the park to the people who live here. The site’s pastoral character provides the opportunity to get away from the nearby urban milieu. From Patzman Street with views to the cityscape a mere mile to the east, one descends into the park to become surrounded by majestic native hardwood trees. From a mid-point on this dramatic slope, one is able to look to the north across a lake to the dense growth of a riparian landscape along the banks of Twelve Mile Bayou, with no sense of the industrial district beyond. SWEPCO Park has provided several generations of citizens a place to hold family reunions, to slide down a steep hill, swing away, spin round and round, or just sit on a bench to contemplate the divide between man and nature.

Figure Nine: View looking north along Webster Street towards Patzman Street and SWEPCO Park. The wood fence indicates the steep slope at the top of the park. The cooling pond in the distance is visible through a portion of the fence. On the other side of the fence are the canopy trees above the park’s west edge. The concrete retaining walls on the right side of photo

Figure Ten: View looking east along Patzman Street toward Shreveport’s central business district. The left side of the street is the top of SWEPCO Park. Prior to the implementation of the street and storm water infrastructure project circa 1960, the crest of the hill in the photo’s middle ground marked the discontinuation of Patzman Street as it approached the crest of the hill. The concrete retaining wall visible here and the previous photo suggest that a continuous sloping grade connected what is now the park to the location of the fort just off the right of this image.

History: Part One

SWEPCO Park officially became a park of the City of Shreveport in 1969 when Shreveport Mayor Clyde E. Fant signed Resolution No. 148 “to accept on behalf of the City of Shreveport for the purposes of furthering and expanding the recreational, cultural and aesthetic development of said City, and for the particular purpose of the use and enjoyment of public parks and recreational areas within the City, a donation unto the City from the Southwestern Electric Power Company.” (SWEPCO) For most of SWEPCO Park’s forty-eight year existence, however, the City of Shreveport has largely neglected it, most likely because the park resides in the low-income, majority-black neighborhood called Allendale. The evidence of SWEPCO Park’s neglect largely stems from the lack of it being mentioned in parks department master plans and in local newspaper articles on the Allendale neighborhood, many of which addressed the topic of the City’s attempts to revitalize Allendale over the past forty years.

The agency responsible for city parks, Shreveport Public Assembly and Recreation (SPAR), began installing recreation equipment in SWEPCO Park during the 1970s, during a period of significant development of the City’s parks. An article in the Shreveport Journal on March 16, 1976, states that SPAR had “developed a master plan for each park,” listing SWEPCO Park under the heading “Neighborhood Parks.” This same article offered the following description: “Six acres donated by SWEPCO, will serve approximately 10,000 people; will have full-size basketball court with six goals; unsupervised play.”8 Playground equipment, benches, barbecues, and the basketball court were set up during this period. Prior to being elected mayor of Shreveport, Cedric Glover succeeded in erecting the covered pavilion in SWEPCO Park in the 1990s, while serving as city councilman representing the Allendale neighborhood.

SWEPCO Park’s historical significance to the city and to the state is rooted in the history of the neighborhood surrounding it and in the landscape within it. For one, a Civil War fort is located partially on SWEPCO Park, the Confederate Fort Sidney Allen Johnston. It resides in Allendale, one of Shreveport’s oldest and most historically rich neighborhoods, where the Civil Rights movement was launched and mostly carried out. SWEPCO Park is also the center of a heated issue in Shreveport today: its presence in Allendale is keeping an interstate highway from being built through the neighborhood, which would surely lead to the neighborhood’s devastation.

Part Two

Shreveport became important strategically for the Confederacy during the last years of the Civil War, politically, economically and militarily, especially since Union forces had captured most of southern Louisiana by then. The city was the headquarters of the Trans-Mississippi Department of the Confederate Army, and in May 1863, Shreveport became capital of the State of Louisiana. It was also “a vital point for the transfer of cotton, cash, and armaments to and from different parts of the Confederate States.”9 Because of its increased importance, it was expected Union forces would attack it, and the city and Confederate forces built “[a] series of forts, defensive lines, trenches, and batteries… around the city.”10 During the spring of 1864, hundreds of slaves from plantations in Caddo and Bossier Parishes were forced to build, expand, and augment defensive structures throughout the city.11 They include Fort Turnbull (later called Fort Humbug), Fort Jenkins, Camp Boggs, and most importantly for this report, Fort Albert Sidney Johnston, which “stood on the present site of the SWEPCO Park at Webster and Clay Streets in the Allendale area.”12 Approximately seventeen batteries were constructed to fill “gaps between the forts, providing enfilading fire.” Battery Twelve was located “at the end of Pierre Avenue, on the elevated portion of the SWEPCO plant, erroneously called Arsenal Hill…because the arsenal was actually located where the McNeill pump station stands on Cross Bayou.”13

In his article, “Shreveport’s Civil War Defenses,” local journalist John Andrew Prime describes the three forts as anchors of “a chain of low hills to the south and west of the grid-street layout of the then-small town.”14 The three forts were strategically built on hilltops so that Confederate soldiers could spot Union forces approaching the city along the western bank of the Red River, one of the only dry, unforested areas at the time the Union Army could feasibly use to stage an attack. With the forts and batteries placed as they were, Confederate forces could delay or turn back such an attack. Fort Turnbull was the main defense point, with a boggy marsh called Silver Lake separating it from the town. 15 Fort Jenkins faced south and Fort Johnston faced north and west, so troops in this position could spot Union forces approaching across the solid ground west of the city.

Prime considers only Fort Sidney Albert Johnston of the three forts as remaining “in remarkably good preservation under the streets of north Allendale” because of there being a “lack of modern, destructive renovations, benign neglect and the existence of an old and relatively undeveloped city park,” which is SWEPCO Park.16 There is no direct evidence of the park being “under the streets” of north Allendale, and no recorded archaeological evidence of the fort. What is known of Fort Johnston’s existence comes from accounts passed down to historians and defensive maps of the City of Shreveport. Its location is verified by a map in the Noel Memorial Library Archive at LSU in Shreveport. Known as the “Venables Map” of 1864, named after the officer of the Confederate Engineering Corps responsible for producing it. The map, entitled “Environs of Shreveport and Its Defences,” clearly shows the location of Fort Johnston on a hilltop northwest of the city, situated just above the bayous that meandered across a broad plane immediately north of the site. This map indicates the topography of the city’s environs and reveals a remarkable similarity to the landforms existing today in this area of north Allendale.

Local historian and faculty member at Louisiana State University-Shreveport (LSUS), Dr. Gary Joiner has studied the training received by soldiers at West Point prior to the Civil War. With his knowledge of how forts were laid out during this period, Joiner after surveying the site with Lane Calloway of the Shreveport Historic Preservation Commission, concluded that the two plateaus extant within the park are highly likely contributing elements to the defenses surrounding Fort Johnston. The locations of these landforms are indicated in the site description above. Photos included in this documentation also illustrate these important artifacts.

Part Three

Because the park was a corporate donation to the City of Shreveport, and is named for this gift, knowledge of the roots of this electric utility is a relevant part of the historical narrative. Operating in the region as several smaller utilities, Southwestern Electric Power Company (SWEPCO) was first formed as the Southwestern Gas and Electric Company (Southwestern) in June 1912. The company was the product of a merger between three power companies owned by a trio of brothers, Rufus, Henry and Charles Dawes –- Shreveport Gas, Electric Light and Power Company; Caddo Gas and Oil Company; and Texarkana Gas and Electric Company.17 In the 1920’s Southwestern began construction on its largest power generation plant in Shreveport. The 10,000-kilowatt “giant” of its day Arsenal Hill Power Plant began operating in 1926. In 1928, Southwestern got out of the gas business in 1928, and in the 1930s and early 1940s became involved in “ice, water and streetcars, before divesting of these interests in the late 1940s.”18 Southwestern’s service territory continued to expand, and the company’s original power plant units, including the Arsenal Hill plant, were inadequate to meet growing needs. Southwestern built natural gas-fired plants and added multiple generating units in various locations in the 1940s and 1950s. In 1958, after forty-six years as Southwestern Gas and Electric, the company changed its name to Southwestern Electric Power Company.19 Beginning in the 1960’s changes in the production of oil and natural gas in the United States led to the use of coal, which was inexpensive, abundant and readily available around the country. This change of focus on the type of fossil fuels used to generate electricity may have led SWEPCO to de-accession properties it was no longer using, prompting the donation of land adjacent to its Arsenal Hill plant to the City of Shreveport for use as a city park.

SWEPCO built two new coal plants in the late 1970s and early 1980s, Flint Creek in NW Arkansas, and Welsh in East Texas. The Pirkey Plant in East Texas and the Dolet Hills Power Plant in Louisiana were completed in 1985 and 1986, respectively. In 2000, the American Electric Power merged with SWEPCO to become AEP SWEPCO, functioning as a subsidiary of this corporate giant. In 2006, the company celebrated its 100-year anniversary of operations in Shreveport.

Part Four

SWEPCO Park is located at the northern end of Allendale neighborhood, one of Shreveport’s oldest communities with a correspondingly rich social and cultural history. Today, Allendale effectively encompasses the neighborhoods of Ledbetter Heights (known previously as the Bottoms due to its physical circumstance), and Lakeside, immediately south of Allendale, which lost its identity following the construction of I-20 through a portion of it in the 1960s.20 As previously mentioned Allendale was named after General Henry Watkins Allen who lived here while serving as governor of the Confederate State of Louisiana.21 Perhaps the neighborhood’s most prominent historical figure is C.C. Antoine, Louisiana’s first black Lieutenant Governor, serving in that position during Reconstruction. Antoine’s house was located at 1941 Perrin Street in Allendale, six blocks southwest of the site of SWEPCO Park. He was born free in New Orleans in 1836, moved to Shreveport in 1866, and was elected state senator in 1868, serving until 1872. That year, he became the Louisiana’s Lieutenant Governor. As state senator, Antoine sponsored legislation to establish Shreveport’s first charity hospital, incorporate Shreveport as a city, and built Shreveport’s first city hall in 1872. In 1877, Antoine left office and returned to Shreveport. He died at age eighty-five in his Allendale house. 22 In the 1920s and 1930s, Allendale was a diverse area, with Irish, Italian, Jewish, Green, Syrian and African American residents, many of whom lived in shotgun houses. On September 4, 1925, a terrible fire devastated the neighborhood, destroying most of the structures in a seven block area southeast of the park site.

As many as 200 dwellings were lost, leaving around 1,000 people homeless. A second event, a tornado that hit the neighborhood in 1940, contributed to the reversal of rebuilding efforts.23 Following these catastrophes, the area became ninety-nine percent African American. As one of Shreveport’s predominately African American neighborhoods, Allendale has often had the highest or close to the highest rates of poverty in the city, mostly a consequence of virulent implementation of Jim Crow laws and institutional racism. Long-time Allendale residents say that in the past it was “a thriving neighborhood — a bustling place for business,” with restaurants, churches and clubs featuring live music and dance.24 The time they describe likely stretched from the 1940s to the early 1970s when blacks were barred from patronizing white-owned businesses and even browsing some store windows in nearby downtown. Ironically, this endemic racism led to numerous African Americans owning their own businesses, enabling these individuals to lead and participate in the Civil Rights movement without fear of being fired.

Because many of the prominent black ministers, business owners and residents worked and lived in Allendale, the area became the center of the Civil Rights Movement in Shreveport. Dr. C.O. Simpkins, considered the leader of the movement, resided and practiced dentistry in there. Dr. Simpkins helped form the United Christian Movement (UCM) in 1957 when the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) struggled to operate after the Louisiana Legislature tried to outlaw the organization and use legislation to sabotage its actions.25 The UCM fought Jim Crow laws, launched voter registration efforts beginning in the late 1950s throughout North Louisiana, and formed the Political Action Committee to groom and screen black candidates to run in local elections.26 When Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. came to Shreveport, he often stayed with Dr. Simpkins, or the home of another Allendale resident important local advocate, Ann Brewster, a prominent local advocate and secretary of Shreveport’s chapter of the NAACP.

A close friend of Reverend King, Simpkins served on the board of King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). As head of the UCM, Simpkins hosted SCLC’s annual conference in Shreveport in October 1960.27 Because of Simpkins’ effective leadership and activism, he was frequently targeted with threats and acts of violence. He and his family frequently received threatening phone calls and saw crosses burned in their yard. In 1962, his newly built house and cabin at Lake Bistineau were bombed and destroyed, fortunately while the family was away. His dental office was also bombed. After his medical insurance policies were canceled and he was refused insurance from other local companies, Simpkins moved his family to New York State.28 Martin Luther King spoke several times in Shreveport, delivering all of his sermons or speeches in Allendale churches, which also served as meeting places for the UCM, NAACP, and other Civil Rights organizations. Martin Luther King first spoke in Shreveport at Allendale’s Galilee Baptist Church, built in 1877 by freed slaves, on August 4 1958, his first fully recorded sermon.29 In the documentary film “Beyond Galilee,” about Shreveport’s role in the Civil Rights Movement, Dr. Gary Joiner identified King’s sermon at Galilee as a precursor to King’s “I Have a Dream” speech and “a toolkit” for his audience to use to challenge the segregation and virulent racism in Shreveport and across the South.30 King also spoke at Everest Baptist, Little Union Baptist and Antioch Baptist churches, all located in Allendale as well.

It was the 1958 sermon at Galilee, however, that effectively launched the Civil Rights movement in Shreveport. The event led to King befriending and recruiting several people in addition to Dr. Simpkins, to bring change to North Louisiana, namely Reverend Harry Blake, pastor of Lake Bethlehem Baptist Church and president of Shreveport NAACP and Ann Brewster, who also ran the Modern Beauty Shop with several other Allendale women. King appointed Blake as his field representative for the SCLC. As a result of his friendship and close working relationship with Dr. King, Reverend Blake became a target of the Ku Klux Klan, as well as other city and business leaders. King also met with Brewster and the other women working at Modern Beauty to urge them to spread information about Civil Rights meetings and activities to their clients and have them spread the news into the community.

All of the key events of Shreveport’s Civil Rights movement took place in Allendale. One especially dramatic event was sparked by the deaths of four girls in the bombing on September 15, 1963, of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama. Reverend Blake and other black leaders petitioned Shreveport Commissioner George D’Artois to have a memorial march down Milam Street in Allendale, which D’Artois denied. On September 22, 1963,

“hundreds of blacks met at Booker T. Washington High School to participate in the march” and were met with approximately “200 city policemen, sheriffs, marshals, and other law enforcement officials” who blocked parts of the street.31 About eighty of the marchers took an alternative route that brought them to Little Union Baptist Church, where 300 to 400 black citizens had gathered for a memorial service for the young bombing victims.32 Commissioner D’Artois had ordered a police riot squad at Little Union as well. More than 200 white police officers, on foot and horseback, armed with batons and rifles with bayonets, menaced the crowd outside, pushing them away from the church. Inside, the memorial service was being performed by Reverend C.C. McLain, Blake, and two guests, Clarence Laws, the Southwest Regional Secretary of the NAACP, and most importantly, H.D. Coke, a deacon of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham. The presence of these leaders was enough to threaten Commissioner D’Artois and his police force, but they also spoke angrily about the bombing, and about the “‘storm troopers’ outside the door.”33 Tensions soon erupted, resulting in police officers severely beating Reverend Blake on the steps of the church until he fell unconscious. A black medical doctor, Joseph Sarpy, and his wife Maxine, a registered nurse, both new residents of Allendale, were able to treat and stitch the lacerations across Blake’s head.34 Blake was taken to another doctor’s house instead of a local hospital for fear he may not make it out alive.

As Blake was being treated, the mounted Shreveport police officers rode horses up the steps of Little Union and into the church, demonstrating to blacks that even their churches were not sanctuaries. Elsewhere in the neighborhood mounted police rode up steps onto the porches of nearby residents, beating onlooking protestors. Blacks have referred to the events of that day as “the incident.”35 Interestingly, D’Artois and other city leaders kept any mention of “the incident” out of all local print and broadcast media.36 Few white people in Shreveport ever knew that this happened, and those that did kept silent. At the time word spread within the black community, but today not many blacks in Shreveport know of these events. Remarkably, the Shreveport Police Department filmed their actions that night. This footage was recently discovered and incorporated into documentary films and TV news stories about the era.37 The violence and desecration of Little Union during those three days galvanized many blacks into action. In response to Blake’s beating, hundreds of black students staged protests at Booker T. Washington High School on Monday, September 23, 1963. When they began marching down Milam Street toward downtown Shreveport, the police moved in, beating many and throwing them into paddy wagons. Another protest of 700 students occurred the next day at J.S. Clark Junior High School and was quelled by three black police officers.38 From 1964 to 1968, blacks acted to ensure Shreveport implement the Civil Rights Act.

Allendale resident Maxine Sarpy resigned from her registered nurse position “at Schumpert Hospital to protest the racial segregation of patients and the denial of permission for black physicians to practice there.”39 Sarpy also led numerous voter registration drives and was invited to President Johnson’s signing of the Voters Act of 1965. Shreveport was still slow to enact it. Blacks began staging boycotts of stores where they still weren’t being served or were only being hired for menial jobs. The desegregation of Caddo Parish schools proved the most difficult endeavor. Not until 1965 were the first black students allowed to attend an all-white school. In May 1972, a suit was filed against the Caddo Parish school board, essentially accusing it of failing to desegregate its schools.40 While the Civil Rights movement in Shreveport undeniably brought positive changes for blacks, it also unintentionally disrupted the fabric of many black communities and sadly, led to more impoverishment. This was especially true in Allendale and Ledbetter Heights. In the 1970s, people began vacating the neighborhood. According to the US Census Bureau, Allendale lost two-thirds of its population between 1970 and 2000, from 16,274 to 5,982. Many of those who moved, abandoned their houses and places of business, which then became havens for criminal activity, including illegal drug trade, drug abuse, prostitution, and gang violence. A city councilman serving Allendale, Calvin Lester, blamed this outmigration on young people moving out once they increased their income.41 By 2005, much of the property in Allendale was adjudicated. The neighborhood had become what was essentially an inner-city ghetto, rife with crime within the dilapidated houses and abandoned structures.

Also in 2005 seeing an excellent opportunity to realize its mission, Community Renewal International (CRI) with the Fuller Center for Housing began building new houses in the area around SWEPCO Park. These residences were then offered to working, low-income families with interest-free mortgages. These efforts continue today, reducing crime and radically altering the quality of life in this part of the neighborhood.43

Part Five

Around 2016-2018, the City of Shreveport has finally focused on SWEPCO Park because it now desires to decommission it and remove its city park status. This stems from a five year-long heated controversy over the building of an innercity connector (ICC) for Interstate-49 (I-49) to bridge a gap left in the interstate back in the 1990s. Four of the five proposed I-49 ICC routes would cut through Allendale. The I-49 ICC controversy is rooted in Shreveport’s racist past and is essentially a current-day civil rights issue. Those who want to see a through-Allendale ICC are largely made up of white business interests and suburban residents. They are pushing Shreveport Mayor Ollie Tyler, who is African American, and City Councilmen and women, two of whom are African American to have a through-Allendale ICC built. Allendale’s population has remained African American and largely low-income; most of the residents there oppose a through-Allendale route, afraid it will decimate the community.

The I-49 ICC Project began in 2005. City and business leaders and organizations assumed a through-Allendale ICC route would easily be approved. However, on September 9, 2016, the transportation planning agency, the North Louisiana Council of Governments (NLCOG), announced in a public meeting held by Shreveport’s Metropolitan Planning Commission (MPC) it could not recommend any of the five routes for submission to the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA.) All five routes have public or historic entities on them that prevent the routes from passing FHWA regulations. Two of the through-Allendale routes have SWEPCO Park on them; the FHWA prohibits the removal or destruction of city parks in order to build an interstate highway.

After NLCOG’s announcement at the meeting, Shreveport Mayor Ollie Tyler stated she would work with the city parks department (SPAR) to find a way to get the I-49 ICC project back on track. An activist belonging to the group #AllendaleStrong, which opposes the building of a through-Allendale route, interpreted Mayor Tyler’s comment to mean she was going to try to decommission SWEPCO Park, so it could not be an obstacle to the two routes it was on being approved by the FHWA. Two #AllendaleStrong members, John Perkins and Brian Salvatore, suspected in early 2016 that the mayor and SPAR were after SWEPCO Park. In February 2016, the two men noticed SWEPCO Park’s playground equipment and barbeque pits that had been in the park for decades were gone. Perkins and Salvatore had been in the park days before and the playground had been there. Nothing had been posted in SWEPCO Park to say they were going to be removed and no Allendale residents had received anything from the City. When Perkins and Salvatore questioned Shreveport Parks and Recreation (SPAR) officials about the removal, they said a lawsuit had been filed against them because the playground equipment was unsafe. Thus far, no one has found out if the lawsuit exists or why barbeque pits had to be removed along with the playground apparatus.

After Mayor Tyler’s announcement at the September 9, 2016 meeting, #AllendaleStrong members became alert to any other changes made to SWEPCO Park and to fight these negative impacts on the neighborhood. Residents observed that SPAR was not maintaining the park, resulting in thigh-high grass and weeds throughout it. Allendale resident and Vice President of #AllendaleStrong Louis Brossett decided to clean up SWEPCO Park himself and began mowing the grass. When a SPAR employee spotted him doing it, he told Brossett he was not allowed to mow the park’s grass because he was not a SPAR employee and therefore not insured for it. It was only after Brossett and other activists informed SPAR they had called the media to document the city’s neglect of the park that employees were directed to mow and perform other minor maintenance. Media did report on the incident.43 On November 15, 2016, Brossett said an unknown person texted him that s/he had heard SPAR was planning to remove SWEPCO Park’s pavilion. No date was provided. The next morning Brossett and other concerned citizens stood in vigilance near the pavilion, in case a SPAR crew showed up to dismantle it. They called Ronnie Hammond, Assistant Director of SPAR and other staff to confirm whether the plan was real. Hammond, SPAR Director Shelly Ragle, and the Mayor’s office all denied that there were plans to remove the pavilion.

Allendale residents gathered that evening in SWEPCO Park to prevent any attempts to remove the pavilion and to show they knew what the city was up to. In their effort to save the neighborhood, members of #AllendaleStrong researched the rules and procedures used by both the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) and US Department of Transportation to decide the preferred routes of new highways. John Perkins, #AllendaleStrong member, filed a Freedom of Information Act request for city government documents on SWEPCO Park.44 Email correspondence dating back to at least April 2016, among Mayor Tyler, SPAR staff and Providence Engineering, the firm hired to conduct feasibility studies of the Inner-City Connector (ICC), confirm that it was in the best interest of the City to eliminate SWEPCO Park for the explicit purpose of getting approval by the FHWA for the highway’s construction through the neighborhood. An April 2016, email from a SPAR employee stated that Director Ragle wanted all park amenities to be removed for “the demolition” of SWEPCO Park, one of the key features within the proposed routes of the ICC that would limit approval of the highway project. Perkins has submitted this evidence of collusion between city officials to close the park to state representatives of the FHWA. The hope of these activists is that this proof of manipulating the rules for the sake of politics will result in any of the routes through Allendale will be removed from consideration.45

A final condition that must now be considered is the existence of Fort Sidney Albert Johnston along the path of the highway, and in particular a significant portion of these fortifications remaining is SWEPCO Park. The group has contacted the Shreveport Historic Preservation Commission about having the fort certified as a protected historic site. Once a protected historic site, this will also prevent the routes through the park from receiving approval by FHWA. The irony that a Confederate fort would keep a black neighborhood from being decimated is not lost on any of the Allendale residents and others opposed to I-49 ICC through the neighborhood.

Conclusion

Allendale’s history from the Civil War, the era of Civil Rights, and post-Civil Rights period have all converged to make this small, neglected park a significant landmark for the City of Shreveport. Wealthy white business leaders, city residents, as well as black leaders, who stand to benefit from the completion of I-49 through the inner-city, were all convinced that this project was a foregone conclusion. Most of Shreveport had written off Allendale even after the Fuller Center and CRI began revitalizing the neighborhood. They did not anticipate that opposition to the highway by the area’s low-income black residents would have any chance of success. #AllendaleStrong has made the I-49 ICC a modern civil rights issue: a challenge to the inherent racist institutions in a city that has always been reluctant and slow to change.

Sources: Citations 2017_SWEPCO Park_Final_Reduced HALS