Ballpark Mural tells stories of Shreveport’s African American Community

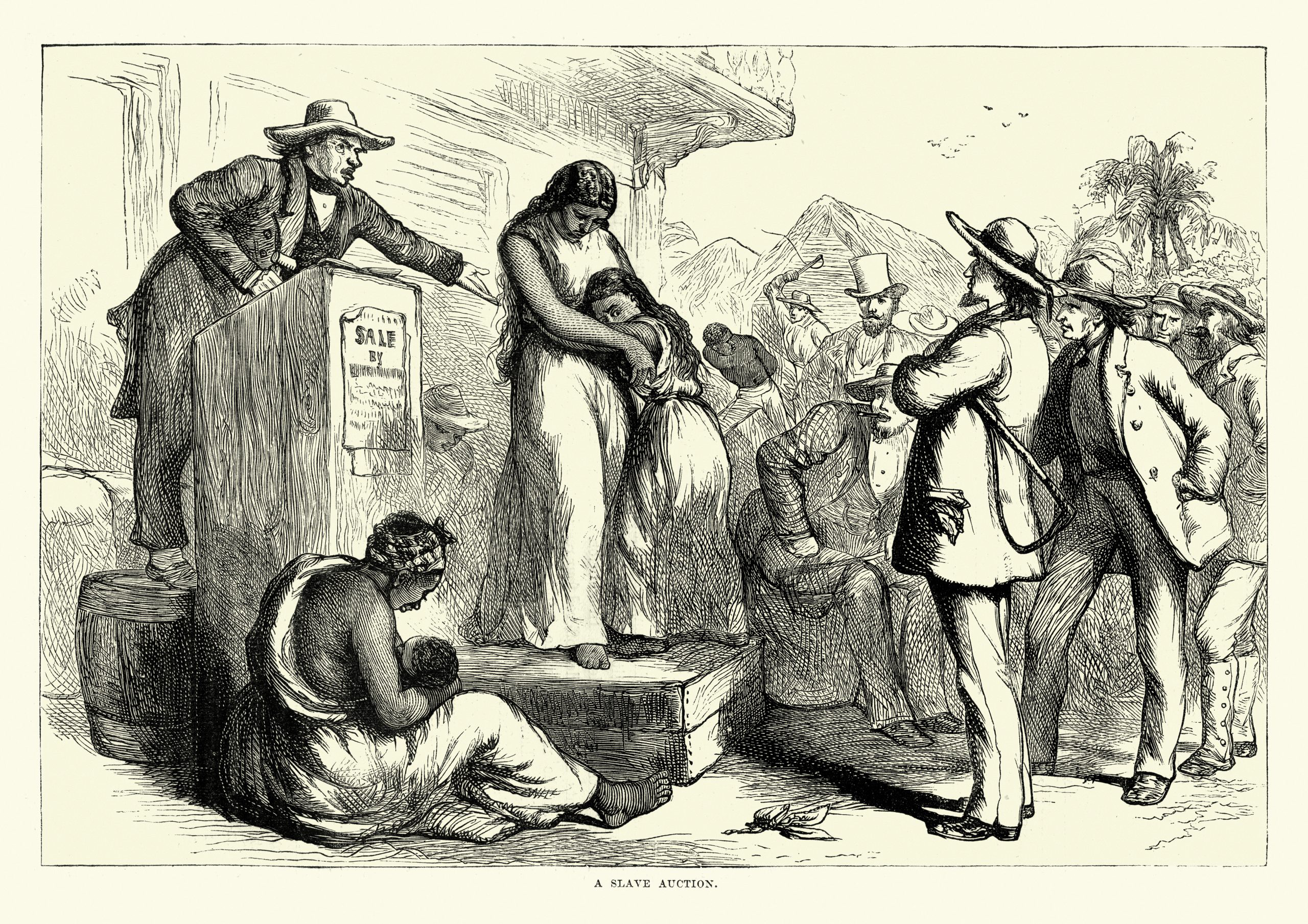

Galilee’s Stewart-Belle Stadium mural was sponsored by the Shreveport Commission on Race and Cultural Diversity. It is intended to reflect the persistence, resilience and hopes of the communities of Allendale, Lakeside, and Ledbetter Heights. Many of these residents and many throughout the Shreveport area are descendants of enslaved people, and some of their rich and compelling history is told through imagery in the mural.

Galilee’s Stewart-Belle Stadium mural was sponsored by the Shreveport Commission on Race and Cultural Diversity. It is intended to reflect the persistence, resilience and hopes of the communities of Allendale, Lakeside, and Ledbetter Heights. Many of these residents and many throughout the Shreveport area are descendants of enslaved people, and some of their rich and compelling history is told through imagery in the mural.

The mural begins in Africa, where the human species first emerged, with the Adinkra symbol for “Welcome” inside a mandala placed over a sunset. Adinkra are African decorative representations of traditional ideas and wisdom and are often found in art and architecture. The silhouette of an Acacia tree, which is native to Africa, follows with two figures representing their deep grief when loved ones disappeared, never to return home again; their ancestral links broken, lost to the trans-Atlantic slave trade which was the largest long-distance forced movement of people in recorded history. From the sixteenth to the late nineteenth centuries, at least 12 million African men, women, and children were enslaved and transported to the Americas.

The mural depicts a beautiful woman of color nearly immersed in water which becomes a crashing wave, representing the Middle Passage. Historians tell us that from 10 to 19 percent of those forced onto the Middle Passage died. A fist breaking through chains emerges although some chains remain. You will notice, here, the first butterfly of many throughout the mural representing change and metamorphosis.

The mural depicts a beautiful woman of color nearly immersed in water which becomes a crashing wave, representing the Middle Passage. Historians tell us that from 10 to 19 percent of those forced onto the Middle Passage died. A fist breaking through chains emerges although some chains remain. You will notice, here, the first butterfly of many throughout the mural representing change and metamorphosis.

The official Juneteenth flag is a symbolic representation of the end of slavery in the United States. It represents the continuous commitment in our country to do better and live up to the American ideal of liberty and justice for all. The women dance to celebrate the national holiday.

The official Juneteenth flag is a symbolic representation of the end of slavery in the United States. It represents the continuous commitment in our country to do better and live up to the American ideal of liberty and justice for all. The women dance to celebrate the national holiday.

The decade after emancipation is known as Reconstruction. During that brief time, African American citizens developed schools, started businesses, and entered politics with the hope of being full and equal American citizens. The magnolia flower shifts the focus locally to the historic community of Allendale.

C.C. Antoine, a free man of color prior to the Civil War, moved to Allendale from New Orleans to open a grocery store and live on his farm. A replica of the house he lived in is being built on the location that still remains today. Antoine was an impressive man, a former Union Captain who raised a company of African American soldiers, served as

C.C. Antoine, a free man of color prior to the Civil War, moved to Allendale from New Orleans to open a grocery store and live on his farm. A replica of the house he lived in is being built on the location that still remains today. Antoine was an impressive man, a former Union Captain who raised a company of African American soldiers, served as

Lieutenant Governor of Louisiana during Reconstruction and later became a state legislator for Caddo Parish. He was also president of the Citizen’s Committee that devised a strategy to oppose Louisiana’s Separate Car Act of 1890 segregating railroad passengers. The committee’s objective was to use civil dissent to confront the law and prevent the states from abolishing the suffrage and equal rights gained by African American citizens during Reconstruction. The plan and resulting proceedings became the Supreme Court case Plessy v. Ferguson in which the court would uphold the constitutionality of racial segregation under the “separate but equal” doctrine. This court decision is noted in the mural over a falling butterfly threatened by a black crow. Crows will be repeated through the mural representing oppression and Jim Crow laws.

The colorful row houses depict Ledbetter Heights which was a red-light district known as “the Bottoms” in the early 1900s. Blues musician Huddie “Leadbelly” Ledbetter began exploring the area on his own at age 16 and later wrote “Mister Tom Hughes Town” telling a story of visiting the Bottoms against his mother’s wishes. Above the houses are crows and music notes juxtaposing the creative expression and societal oppression of the emerging African American community.

The colorful row houses depict Ledbetter Heights which was a red-light district known as “the Bottoms” in the early 1900s. Blues musician Huddie “Leadbelly” Ledbetter began exploring the area on his own at age 16 and later wrote “Mister Tom Hughes Town” telling a story of visiting the Bottoms against his mother’s wishes. Above the houses are crows and music notes juxtaposing the creative expression and societal oppression of the emerging African American community.

In 1923, Cora Murdock Allen, wife of prominent Baptist Minister the Rev. Luke Allen Jr. and a well-respected business woman, leader and speaker of women’s rights and civil rights was the visionary leader, along with nine African American women and one African American man that spearheaded the design and construction of the Calanthean Temple on Texas Avenue, also known as “The Avenue.” The Calanthean Temple, the first fraternal temple in the United States to be built for and managed by a group of

In 1923, Cora Murdock Allen, wife of prominent Baptist Minister the Rev. Luke Allen Jr. and a well-respected business woman, leader and speaker of women’s rights and civil rights was the visionary leader, along with nine African American women and one African American man that spearheaded the design and construction of the Calanthean Temple on Texas Avenue, also known as “The Avenue.” The Calanthean Temple, the first fraternal temple in the United States to be built for and managed by a group of

African American women, was a thriving center of African American business and social life. By night, famous musicians such as Louis Armstrong and Duke Ellington performed on the rooftop garden. By day, businesses such as physicians, attorneys, insurance companies, real estate offices, and a beauty school operated, at a time when segregation prevented black professionals from working downtown. When originally built, it was the tallest building in Shreveport at four stories. Unable to find clear photos of Mrs. Allen, we took artistic liberty with her image, but her representation is in front of the framing of the rooftop garden on the temple, which still stands today. Musicians are depicted to her left and professionals to her right. A butterfly rests on her arm. “The Avenue” has been called Shreveport’s version of the Harlem Renaissance or our Black Wall Street. Such businesses as the Freeman and Harris Restaurant, the Star Theatre and the Shreveport Sun Newspaper were initially established on The Avenue.

Between the images of Cora M. Allen and Antioch Baptist Church is a poem by Gwendolyn Brooks, who was the first African American Pulitzer Prize winner for her poetry which reflected both a commitment to racial equality and masterful poetic skills. “We are each other’s harvest we are each other’s business; we are each other’s magnitude and bond.”

Between the images of Cora M. Allen and Antioch Baptist Church is a poem by Gwendolyn Brooks, who was the first African American Pulitzer Prize winner for her poetry which reflected both a commitment to racial equality and masterful poetic skills. “We are each other’s harvest we are each other’s business; we are each other’s magnitude and bond.”

In The Blacker the Berry, Southern University at Shreveport Professor Willie Burton wrote about the significance of the church in the African American community. It was not only a place of spiritual guidance, but also a center of community and social activities, education, and support. At Antioch Baptist Church, the African American community had a place where they could develop politically and professionally, as well as spiritually. Burton identifies Antioch as the “Mother Church” for African American Baptists in Shreveport because it was the first church established and because many other African American churches were developed from it. The current Antioch Baptist Church on Texas Avenue, just down the street from the Calanthean Temple, was built in 1901.

As African American businesses began to thrive, they moved further down the street to Pierre Avenue, Milam Street, and other adjacent streets in Allendale. Throughout the 1950s this area was a uniquely mixed neighborhood with residents of Italian, Greek, Jewish and African American ethnicities.

Residents can remember businesses such as Henrietta’s Beauty School, Benevolent Funeral Home, Fraternal Funeral Home, St. Paul’s Church, the Mercy Sanatorium, Wilson’s Tailoring, the Negro Chamber of Commerce, Modern Cleaners, Modern Beauty, The Pierre Avenue Grill, and the Harlem House Restaurant. Because we were unable to locate photographs of the area during that time and few buildings remain, we represented the area as a flowering tree to capture its vibrancy. A crow sits on the street sign, on the ground in front of the tree, and flies above.

Residents can remember businesses such as Henrietta’s Beauty School, Benevolent Funeral Home, Fraternal Funeral Home, St. Paul’s Church, the Mercy Sanatorium, Wilson’s Tailoring, the Negro Chamber of Commerce, Modern Cleaners, Modern Beauty, The Pierre Avenue Grill, and the Harlem House Restaurant. Because we were unable to locate photographs of the area during that time and few buildings remain, we represented the area as a flowering tree to capture its vibrancy. A crow sits on the street sign, on the ground in front of the tree, and flies above.

In the 1950’s the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People began challenging segregation laws in public schools. In 1954, the case of Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka revisited “separate but equal” and declared it to be unconstitutional. The ruling is considered a cornerstone of the Civil Rights movement and helped establish the precedent that would be used to overturn the laws enforcing segregation. A young African American girl walks along the mural. She represents Ruby Bridges, the first African American child to desegregate an all-white elementary school in New Orleans. She was also the inspiration for Norman Rockwell’s painting “The problem we all live with.” The young girl in the mural stands for all the children who were the first to segregate their schools, like Shreveport’s own Carolyn Jones, who at the age of five, was the youngest African American child to integrate Creswell Elementary School in Caddo Parish. She walks past the butterflies and flowers and towards Little Union Baptist Church. A crow flies by and the sky turns red.

Louisiana resisted desegregation and the progress of Civil Rights in the state until the 1960s. According to historian Burton, in 1956, Black teachers in Caddo were warned by their school superintendents not to “attempt to attend LSU nor advocate integration, lest they lose their jobs.” By 1964, however, Caddo and other parishes were ordered to integrate or lose federal funding. In 1965 Arthur Burton and Brenda Braggs became the first Black students locally to attend an all-white school when they enrolled in C.E. Byrd High School.

Louisiana resisted desegregation and the progress of Civil Rights in the state until the 1960s. According to historian Burton, in 1956, Black teachers in Caddo were warned by their school superintendents not to “attempt to attend LSU nor advocate integration, lest they lose their jobs.” By 1964, however, Caddo and other parishes were ordered to integrate or lose federal funding. In 1965 Arthur Burton and Brenda Braggs became the first Black students locally to attend an all-white school when they enrolled in C.E. Byrd High School.

Consider the segregation that existed in Shreveport in 1964. White and Colored signs were over trolley and bus seats, on restrooms, water fountains, waiting rooms, restaurant entrances and other public places. Hospitals had separate wards or offered no services to Black citizens at all.

In September 1963, the Reverend Dr. Harry Blake, then president of the Shreveport chapter of the NAACP, held a memorial at Little Union Baptist Church for four young girls killed in a church bombing in Birmingham Alabama. President Kennedy had announced a National Day of Mourning for the girls. During the memorial service, the church was surrounded by armed police from the Shreveport Police Department, many on horses. One horse was led directly into the church and Rev. Blake was beaten nearly to death. Many in the African American community were outraged, but not surprised. While they were devastated, they were ready to stand up for their rights. The horse in the mural is inspired by Picasso’s painting, Guernica, which expressed opposition to fascism and war.

For three days following the violent police attack at Little Union Baptist Church, students from Booker T. Washington High School and J. S. Clark Junior High protested and were beaten, tear-gassed, arrested and jailed. Calvin Austin remained in jail longer than any student protester and was not allowed to return to Booker T. Washington High School or any other local school to complete his education or graduate. Protests and demonstrations continued throughout the 60’s in which African American citizens stood up for equal employment opportunities, equal access to Shreveport’s downtown library, fair voter registration and equal representation in the government. The protests are represented on the mural following Little Union.

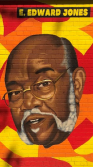

Here you see the images of local legends who were integral to the Civil Rights Movement of the 60s and who remained leaders in Shreveport throughout their lives. These individuals represent the many local Civil Rights leaders and activists who stood up to be recognized as full and equal American citizens.

The Reverend Dr. E. Edward Jones was pastor of Galilee Baptist Church for nearly six decades and a man of accomplishment. He was a spiritual leader, a Civil Rights activist, a visionary and pillar of the community. Rev. Jones was an untiring advocate for the development of housing, education, and economic stability for the Black community. Ebony called him one of the nation’s most influential African American leaders. He and his wife, Leslie Jones, filed the suit that compelled desegregation of public schools in Caddo Parish and their youngest daughter Carolyn was the first African American child to integrate Creswell Elementary School. He envisioned and built Galilee City, a church-based community for the poor and disenfranchised. Among his many services to Shreveport and Louisiana include sitting on the Caddo Parish Police Jury, leadership as President of the National Baptist Convention of America, and his membership on the LSU Board of Supervisors.

The Reverend Dr. E. Edward Jones was pastor of Galilee Baptist Church for nearly six decades and a man of accomplishment. He was a spiritual leader, a Civil Rights activist, a visionary and pillar of the community. Rev. Jones was an untiring advocate for the development of housing, education, and economic stability for the Black community. Ebony called him one of the nation’s most influential African American leaders. He and his wife, Leslie Jones, filed the suit that compelled desegregation of public schools in Caddo Parish and their youngest daughter Carolyn was the first African American child to integrate Creswell Elementary School. He envisioned and built Galilee City, a church-based community for the poor and disenfranchised. Among his many services to Shreveport and Louisiana include sitting on the Caddo Parish Police Jury, leadership as President of the National Baptist Convention of America, and his membership on the LSU Board of Supervisors.

Dr. C. O. Simpkins was a dentist and a founding member of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference in the 1950s, serving closely with his friend, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. He is known as the father of the Civil Rights Movement in North Louisiana. Dr. Simpkins was active in securing voting rights for Shreveport African Americans as the founder of the United Christian Conference on Registration and Voting prior to the Voter’s Rights Act of 1965. As a result of his activism, Simpkins was harassed and arrested, his home and dental office were firebombed, and finally his medical insurance was cancelled. As a result, he left Shreveport for New York where he established another dental practice and continued his advocacy for Civil Rights. He returned to Shreveport 26 years later, re-engaging in politics and in 1991 was elected to the Louisiana Legislature.

Dr. C. O. Simpkins was a dentist and a founding member of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference in the 1950s, serving closely with his friend, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. He is known as the father of the Civil Rights Movement in North Louisiana. Dr. Simpkins was active in securing voting rights for Shreveport African Americans as the founder of the United Christian Conference on Registration and Voting prior to the Voter’s Rights Act of 1965. As a result of his activism, Simpkins was harassed and arrested, his home and dental office were firebombed, and finally his medical insurance was cancelled. As a result, he left Shreveport for New York where he established another dental practice and continued his advocacy for Civil Rights. He returned to Shreveport 26 years later, re-engaging in politics and in 1991 was elected to the Louisiana Legislature.

The Reverend Dr. Claude Clifford McLain became pastor of the Little Union Baptist Church in 1959 and faithfully served that congregation for 32 years. He was a dynamic leader and a prominent force in the Civil Rights movement here, serving as president of the Shreveport chapter of the NAACP. At McLain’s invitation, Dr. King spoke at Little Union in 1962 at a voter registration rally. Rev. McLain was the pastor of Little Union on the night Rev. Blake was beaten, and the church desecrated. Threats of violence were a regular occurrence for the McLain family, as Little Union Baptist Church became the epicenter of the Civil Rights movement in Shreveport in the 1960s.

The Reverend Dr. Claude Clifford McLain became pastor of the Little Union Baptist Church in 1959 and faithfully served that congregation for 32 years. He was a dynamic leader and a prominent force in the Civil Rights movement here, serving as president of the Shreveport chapter of the NAACP. At McLain’s invitation, Dr. King spoke at Little Union in 1962 at a voter registration rally. Rev. McLain was the pastor of Little Union on the night Rev. Blake was beaten, and the church desecrated. Threats of violence were a regular occurrence for the McLain family, as Little Union Baptist Church became the epicenter of the Civil Rights movement in Shreveport in the 1960s.

The Reverend Dr. Harry Blake was raised on a plantation in Northeast Louisiana under the sharecropper system. He met Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. when he was 23. By age 25, he was a field representative for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, which adopted nonviolent action as the cornerstone of integration through civil dissent. Dr. Blake’s work as a pioneer of Civil Rights made him dangerous to segregationists and city officials. He was arrested and his life threatened many times. Rev. Blake was Pastor Emeritus of the historic Mount Canaan Baptist Church in Shreveport and served 15 years as president of the Louisiana Missionary Baptist State Convention.

The Reverend Dr. Harry Blake was raised on a plantation in Northeast Louisiana under the sharecropper system. He met Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. when he was 23. By age 25, he was a field representative for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, which adopted nonviolent action as the cornerstone of integration through civil dissent. Dr. Blake’s work as a pioneer of Civil Rights made him dangerous to segregationists and city officials. He was arrested and his life threatened many times. Rev. Blake was Pastor Emeritus of the historic Mount Canaan Baptist Church in Shreveport and served 15 years as president of the Louisiana Missionary Baptist State Convention.

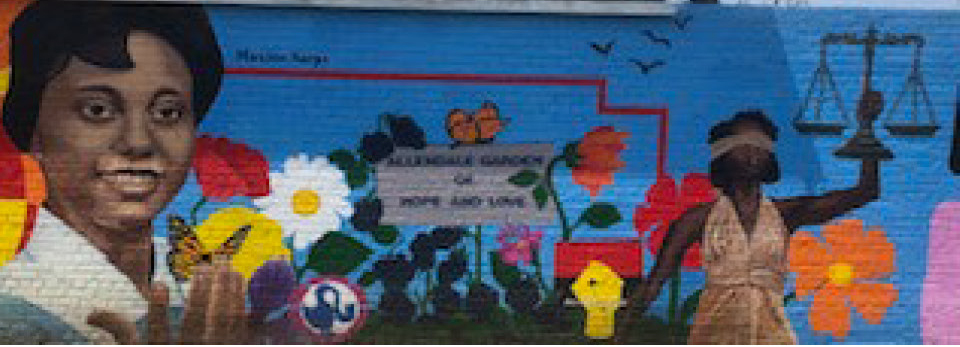

Mrs. Maxine Sarpy holds a butterfly in her hand representing her view of change grounded in love that was inspired by Dr. King. Originally from Texas, she was one of the first African American students to graduate from the University of Texas School of Nursing. She was also an instructor at the university until she married Dr. Joseph Sarpy Jr. and moved to Shreveport. Two weeks after arriving, she witnessed firsthand the violation of Little Union Baptist Church. Mrs. Sharpy and her husband, Dr. Sarpy, rushed to the side of Rev. Harry Blake to treat his injuries and her passion for Civil Rights was ignited. Within months, Mrs. Sarpy was working with Ms. Ann Brewster of the local NAACP on a voter registration campaign which she later co-chaired with Dr. Leon Tarver. In 1966, Mrs. Sarpy was one of two people from the 13 southern states involved in voter registration that were invited to Washington, D.C. for a conference. In 1970, she and her husband and other African American activists were among the original members of the organization, Blacks United for Lasting Leadership that initiated the suit against the City of Shreveport for a change in city government, affording African Americans an opportunity to serve on the city council and all branches of city government. Dr. Louis Pendleton was president of the organization and Hilry Huckaby was the attorney who filed the suit representing the organization. During this trial, Mrs. Sarpy was interviewed by Attorney Huckaby and the suit was successful. In 1984, she became the first woman to serve on Shreveport’s City Council. Mrs. Sarpy presided over many Civil Rights and community organizations including the Shreveport Mayor’s Women’s Commission, Caddo-Bossier Port Commission, the State Fair of Louisiana Board, the Community Foundation of Northwest Louisiana, the Fellowship of Christians and Jews, the Shreveport Chapter of Links, an international volunteer service organization of professional women of African descent, and a proud member of the Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority. Mrs. Sarpy's long fight for justice and change is represented by the butterfly, symbolizing her approach of creating change through love and peace.

Mrs. Maxine Sarpy holds a butterfly in her hand representing her view of change grounded in love that was inspired by Dr. King. Originally from Texas, she was one of the first African American students to graduate from the University of Texas School of Nursing. She was also an instructor at the university until she married Dr. Joseph Sarpy Jr. and moved to Shreveport. Two weeks after arriving, she witnessed firsthand the violation of Little Union Baptist Church. Mrs. Sharpy and her husband, Dr. Sarpy, rushed to the side of Rev. Harry Blake to treat his injuries and her passion for Civil Rights was ignited. Within months, Mrs. Sarpy was working with Ms. Ann Brewster of the local NAACP on a voter registration campaign which she later co-chaired with Dr. Leon Tarver. In 1966, Mrs. Sarpy was one of two people from the 13 southern states involved in voter registration that were invited to Washington, D.C. for a conference. In 1970, she and her husband and other African American activists were among the original members of the organization, Blacks United for Lasting Leadership that initiated the suit against the City of Shreveport for a change in city government, affording African Americans an opportunity to serve on the city council and all branches of city government. Dr. Louis Pendleton was president of the organization and Hilry Huckaby was the attorney who filed the suit representing the organization. During this trial, Mrs. Sarpy was interviewed by Attorney Huckaby and the suit was successful. In 1984, she became the first woman to serve on Shreveport’s City Council. Mrs. Sarpy presided over many Civil Rights and community organizations including the Shreveport Mayor’s Women’s Commission, Caddo-Bossier Port Commission, the State Fair of Louisiana Board, the Community Foundation of Northwest Louisiana, the Fellowship of Christians and Jews, the Shreveport Chapter of Links, an international volunteer service organization of professional women of African descent, and a proud member of the Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority. Mrs. Sarpy's long fight for justice and change is represented by the butterfly, symbolizing her approach of creating change through love and peace.

When the Interstate 20 was built in Shreveport in the late 1950s, Allendale was cut off from the rest of the city. Shortly after came the crack epidemic of the 1980s. African American communities were disproportionately affected by the drug surge and the nation’s response which was to arrest and incarcerate addicts, which devastated an already struggling community. For many reasons, between 1970 and 2000, Allendale would lose two thirds of its population. Rosie Chaffold’s Garden of Hope and Love was a harbinger for Allendale’s gradual renewal which continues today. She started her garden in a vacant lot that had been used to dump trash and do drug deals. With the owner’s permission, she planted flowers and vegetables and brought beauty to a community that had seen far too much ugliness. Initially the drug dealers threatened Mrs. Chaffold’s life, shooting out windows in her house and setting her garage on fire. Still, she persisted, eventually winning over the drug dealers who eventually left the neighborhood. In the mural’s Garden are many symbols typifying the community’s resilience and persistence.

On the right of the garden sign is “Blue Goose,” which represents Crosstown, thought to be the first Black settlement in Shreveport after the Civil War. It was located just South of Texas Avenue where I-20 is now. The community was known as Blue Goose because of a painting of a blue goose on a grocery store and place of music and libation. Directly across from the Blue Goose sign is the logo for Allendale Strong, a group of citizens aligned by prioritizing caring relationships connected across all lines of difference. They are against I-49 further cutting up the community, polluting the environment, and destroying historical landmarks.

You can see blackberries growing around the sign for the Garden of Hope and Love paying homage to Professor Willie Burton’s The Blacker the Berry: A Black History of Shreveport. His book was invaluable to our research for this mural. A pink flower to the left of the sign represents Pamoja Arts Society, which was created in 1974 to celebrate African American culture, promote African American artists in the Shreveport-Bossier area, and give them a space to explore cultural themes while developing their professional abilities.

Above the sign, a butterfly rests and above that is a red line. The red line represents “redlining” which is a discriminatory practice by which banks, insurance, and mortgage companies refuse or limit loans, mortgages and insurance within specific geographic areas, usually inner-city and majority African American neighborhoods. In reverse redlining, banks may engage in predatory lending in the same neighborhoods that were once marked as off-limits for borrowers. These practices have resulted in undervalued homes and loss of wealth within the African American community. Black crows fly off into the distance.

Lady Justice follows with her blindfold, sword, and scale, personifying the moral force in our judicial system. The dehumanizing myth of racial difference survived slavery’s abolition and demanded legally codified segregation. It is at the root of today’s wealth inequities and our mass-incarceration crisis. It endures because we don’t talk about it. Lady Justice demands we confront and end this destructive myth.

Our hopes and dreams include a united, equitable, and diverse American culture that continues to strive for a more perfect union and learns to respect and care for each other and the Earth. These ideals are represented by diverse people linking arms, laughing children and multicultural support of the earth.

Our hopes and dreams include a united, equitable, and diverse American culture that continues to strive for a more perfect union and learns to respect and care for each other and the Earth. These ideals are represented by diverse people linking arms, laughing children and multicultural support of the earth.

Riley Stewart and Albert Belle occupy the end of the mural as it rounds a curve to its finish. They came together in the late 1990s to restore the old Texas League/SPAR Baseball Stadium where this mural is painted. Both men were members of Galilee Baptist Church, which traded with the city for the stadium in exchange for the original Galilee Baptist Church building, which will become a Civil Rights museum.

Riley Stewart was a pitcher in the 1940s Negro Leagues. After his baseball career he became a coach and teacher in Shreveport. He was a big man with a big voice and a natural leader. He is a member of the Baseball Hall of Fame and was assistant principal at Airline High School, a member of the school board, a trustee of Galilee Baptist Church, and a community leader.

Riley Stewart was a pitcher in the 1940s Negro Leagues. After his baseball career he became a coach and teacher in Shreveport. He was a big man with a big voice and a natural leader. He is a member of the Baseball Hall of Fame and was assistant principal at Airline High School, a member of the school board, a trustee of Galilee Baptist Church, and a community leader.

Albert Belle was a Major League Baseball outfielder for the Cleveland Indians, Chicago White Sox and Baltimore Orioles. Belle was one of the best power hitters of his generation. In 1995, he became the only player to ever hit 50 doubles and 50 home runs in a season. He was also the first player to break the $10-million-per-year contract in the major league. He lives in Arizona now but remains connected to Shreveport through his family.

The sacrifices, determination, and hard work of the individuals represented in this mural make our lives better today in Shreveport. They have built a foundation on which we can build a brighter future for our community, together.

The mural depicts a beautiful woman of color nearly immersed in water which becomes a crashing wave, representing the Middle Passage. Historians tell us that from 10 to 19 percent of those forced onto the Middle Passage died. A fist breaking through chains emerges although some chains remain. You will notice, here, the first butterfly of many throughout the mural representing change and metamorphosis.

The official Juneteenth flag is a symbolic representation of the end of slavery in the United States. It represents the continuous commitment in our country to do better and live up to the American ideal of liberty and justice for all. The women dance to celebrate the national holiday.

The decade after emancipation is known as Reconstruction. During that brief time, African American citizens developed schools, started businesses, and entered politics with the hope of being full and equal American citizens. The magnolia flower shifts the focus locally to the historic community of Allendale.